Remember This? Ottawa’s world famous dairy

Posted Apr 5, 2021 01:48:00 PM.

CityNews, in partnership with the Historical Society of Ottawa, brings you this weekly feature by Director James Powell, highlighting a moment in the Ottawa's history.

April 8, 1927

Most patrons of the upscale restaurant e18hteen, located in an elegant French-chateau style building just a few minutes walk from Parliament Hill, would be surprised to learn that they were dining in a former dairy.

The building at 18 York St. was originally constructed in 1876 by the Institut canadien-français d’Ottawa as their headquarters.

After a fire gutted it, the building was repurposed, and was for a time used by a pork packer, but for much of its history it was a dairy, producing each year thousands of gallons of homogenized milk, millions of pounds of butter, and crate loads of a processed cheese product that became a global favourite.

The story begins in 1922 with the establishment of the Moyneur Co-Operative Creamery by Charles H. Labarge.

The creamery quickly became of one of the largest in the country, making between 2- and 3-million pounds of butter annually. It also dealt in eggs, poultry and cheese. The business operated out of 12-14 York Street close to the ByWard Market.

In 1925, Labarge established a sister enterprise called the Chateau Cheese Company to produce and market a cheese product that he had developed after many experiments in a corner of his creamery. Chateau Cheese was a pasteurized, soft, cheddar cheese product, similar to Velveeta. (Velveeta was invented by Emil Frey in 1918 and produced by the Munroe Cheese Company in Munroe, New York. The company was sold to Kraft Foods in 1923.) Chateau Cheese could be sliced, spread on crackers and toast, or melted to form a creamy, cheesy topping, ideal for making Welsh rarebit. In addition to the regular cheddar version, a pimento cheese product was also developed.

In August 1925, Chateau Cheese was demonstrated at the Pure Food Show, which was part of the Central Canada Exhibition. At the Moyneur Creamery booth, tempting samples of the cheese spread were offered for tasting. The company advertised that Chateau Cheese would not deteriorate with age. Instead, owing to its superior qualities and scientific manufacture, it would keep indefinitely if a small piece of wax paper was placed over a cut end.

The product was also sold in a variety of convenient sizes, including half-pound packages, which appealed to budget-conscious consumers. This was a marketing innovation as cheese was typically sold at the time in much larger quantities, often as large as five pounds. The company imported specially-made machines from Switzerland that were capable of making the smaller packages. The manufacturing process was totally mechanical, from the production of the cheese to when the boxes slid down the chute to the delivery wagons.

Chateau Cheese found a receptive market.

A half-pound box of the cheesy food was on sale in Ottawa for 23 cents, with additional savings per pound to be had for larger packages. Within short order, it was available across Canada, and could be found in the finest hotels and restaurants.

While conquering the Canadian market, the company also started looking abroad.

The director for sales of Chateau Cheese, Mr. H.D. Marshall, had extensive experience in overseas markets. Under his guidance, Chateau Cheese found its first foreign market in Germany, when the company was less than a year old. Within two years, the cheese was also on sale in Great Britain, the Balkan countries, and even in France — the cheese capital of Europe.

The next market to be tackled was the United States, where sales took off despite a 25 per cent tariff. So popular was Chateau Cheese south of the border that the company began to make the product in Plymouth, Wisconsin.

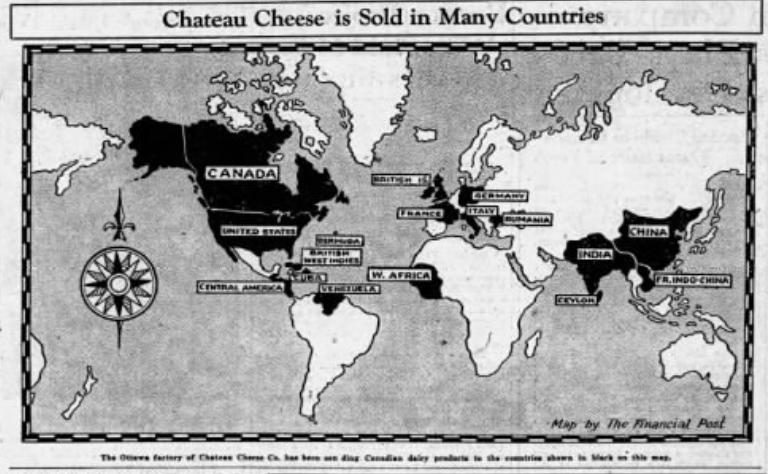

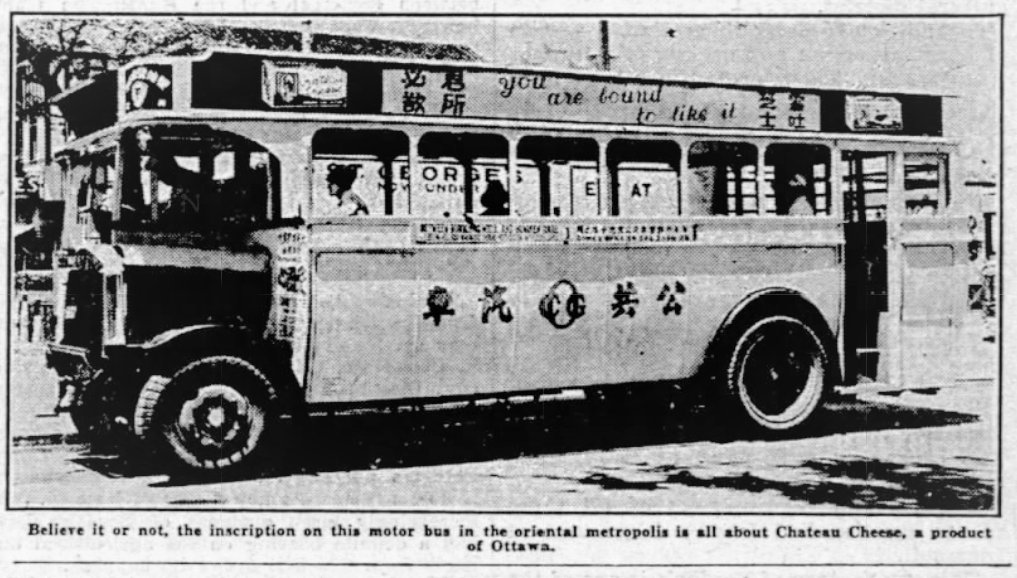

Before long, the cheese was available around the world, with advertisements for Chateau Cheese appearing on billboards in Havana, and on the sides of buses in Hong Kong and Shanghai. It also could be purchased in markets in India, throughout Central America, Bermuda, and parts of western Africa. Chateau Cheese boasted that it was “the cheese that is making Ottawa famous.”

Sales sky-rocketed. In March 1926, cheese sales totalled only $17,000. By October 1928, monthly sales had reached $230,000.

In 1927, Charles Labarge launched the Laurentian Dairy, and purchased 18 York Street, next door to Moyneur Co-Operative Dairy as well as the Baskerville property in the rear to accommodate his growing dairy empire. The three related companies—the Moyneur Co-Operative Dairy, the Chateau Cheese Company and the Laurentian Dairy—together had 233 feet of frontage on York Street with a depth of 165 feet.

The Laurentian Dairy, which was supplied by 125 milk producers in the Ottawa Valley, was the first dairy in North America to sell homogenized milk on a retail basis.

According to an article that appeared in the Journal of Dairy Science in 1963, Laurentian Dairy sold its first bottle of homogenized milk on 8 April 1927; home delivery began ten days later. The Laurentian Dairy advertised that due to its special homogenizing process, cream was prevented from coming to the top but instead was scattered throughout the milk. Its advertising slogan was “The last drop of milk is just as creamy as the first.”

The company later developed and sold an innovative protein milk designed specifically for infants with delicate digestions. The protein milk was sold under a doctor’s prescription. The Laurentian Dairy considered it to be a treatment rather than a food, that should only be taken with the advice of a physician. The dairy claimed that the most dangerous ingredients in cow’s milk—the sugar, whey and whey salt—were removed in the making of the special milk. Protein milk was available for daily delivery on the company’s regular routes through Ottawa and Hull, and sold at a premium price of 30 cents a quart.

In 1928, Laurentian Dairy began selling shares in the enterprise to Ottawa residents. The shares were offered at $50 each with a dividend of 7 per cent. The investments were backed by the combined assets of Moyneur Co-Operative Dairy, the Laurentian Dairy, Chateau Cheese Company and Meadow Milk Products Ltd, another part of the Labarge dairy empire that made condensed milk and milk powder. The total value of the businesses was placed at over $500,000.

In December 1928, Charles Labarge and his partners received an offer they could not refuse from Borden Farm of New York, a major U.S. dairy started in 1857 by Gail Borden.

The American company, which was seeking to expand its Canadian operations, bought the entire enterprise for $3-million—a huge premium over the book value of the firm. Borden’s retained all employees, including Charles Labarge who continued to manage the Ottawa operations.

Chateau Cheese, Laurentian Dairy and their related companies were a perfect fit for Borden’s. Owners of common stock in the Ottawa companies received shares in the Borden Company which were then quoted in New York at $164 dollars a share.

Earlier that same year, Borden Farm Company had also splashed out $1-million to acquire Ottawa Dairy, a locally-owned firm that had started operations in 1900.

The Ottawa Dairy was a large concern with 300 employees, 200 horses, and 100 delivery horse-drawn wagons. It was also the parent company of Cornwall Dairy, a smaller business on the St. Lawrence that employed a further 30 people. Ottawa Dairy owned a model, 800-acre dairy farm in the City View area, roughly one mile south of Baseline Road. This farm stretched from the Prescott Highway (now Prince of Wales) to the Merivale Road. It was stocked with a heard of 300 prime Ayrshire cattle, which provided the company with “nursery milk,” sold at a premium price for babies and invalids.

The old Ottawa Dairy Farm, which became known as Borden Farm after the takeover, remained in operation until 1960.

When Borden’s found it increasingly difficult to operate from the site owing to the encroachment of housing and other developments on all sides, it decided to sell. The straw that seemed to break the camel’s back was a windstorm in 1959 that badly damaged the farm’s barns.

The bulk of the acreage was purchased by the Ontario Department of Planning and Development in co-operation with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation for a housing project. A strip of land 500 hundred feet wide and 1¼ miles long was also bought by the National Capital Commission for a proposed western parkway.

Downtown, the Ottawa Dairy also operated a production facility at 393 Somerset St., just west of Bank Street. This outlet, which produced and sold butter, ice cream and other dairy products under the Borden name, remained in business until 1971 when it too closed owning to cramped conditions. Borden’s moved out to new, modern quarters on St. Laurent Boulevard. The old plant was sold.

The NCC expropriated 18 York St. in 1962 as part of its “Mile of History” plan — a federal centennial project to preserve historic buildings in downtown Ottawa.

Borden’s remained as a tenant in the building until the end of July 1968 when the company got out of the cheese-making business in Canada and stopped producing Chateau Cheese. Fifty employees at the dairy were affected, the majority of whom took early retirement or sought jobs elsewhere. A few found new employment within the firm. For a while, the building was used as temporary storage space. In late November 1970, it was gutted by fire.

The NCC subsequently restored the structure and over the years rented the space to a number of ventures. During the 1980s, it was the home of Guadalaharry’s Tex-Mex restaurant.

The building at 18 York Street has been home to e18hteen since 2001. The NCC has installed a bilingual plaque on the historic building, describing its history.

Borden’s sold its Ottawa dairy facilities to Silverwood Industries in 1980, leaving the Canadian dairy market. As a consequence, Borden’s products vanished from Canadian grocery shelves. Borden Farm, its old dairy farm south of Baseline Road, is now the name of a neighbourhood to the east of Merivale close to Meadowlands Drive.