Tips for conquering seasonal affective disorder in a mental health crisis

Posted Jan 4, 2025 02:30:46 PM.

Last Updated Jan 6, 2025 11:19:38 AM.

Shorter days, and colder temperatures during the winter months, could mean some people fall into a slower routine, more mimicking the hibernation of some our mammal counterparts than the vibrant lifestyles many live in the summer.

Winter weather warnings making it safer to stay in then go out with friends and slippery sidewalks challenging the ability to go out for a walk or run can leave us choosing to stay inside, in our pajamas.

But removing some of these activities that promote physical and social health, our mental health can also take a dip.

The Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) defines seasonal affective disorder (SAD) as “a kind of depression that appears at certain times of the year”. Typically SAD begins in the fall when daylight decreases and continues through the winter.

Many people experience what is often dubbed the “winter blue”, with feelings of lethargy and glumness setting in after the hustle and bustle of the holidays. But SAD can be much more serious.

The Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) reminds Canadians that feeling blue when bad things happen or good things end, is not the same as having a depressive disorder.

“A major depressive disorder lasts for at least two weeks, affecting a person’s ability to work, carry out their usual activities, and have satisfying personal relationships,” it states on it’s website.

According to the CMHA, approximately three per cent of Canadians suffer acutely from SAD, but another 15 per cent experience some symptoms of the disorder.

Symptoms can include low mood, sleeping more than usual, craving sweets and overeating and withdrawing from social interaction.

But while some might wish we could be like bears and sleep through the winter months, there are things you can do to combat symptoms of SAD.

The number one recommendation from the MHCC is allowing yourself to feel your feelings, in moderation. While many may try and mask sadness, crying can actually release endorphins, leaving you feel refreshed afterwards.

Other recommendations include increasing vitamin D intake, whether that be with sun exposure, eating vitamin D rich foods, or taking supplements; practicing your favourite forms of self care, whether that be cooking, cleaning or reading a good book; practicing gratitude; and getting the right amount of sleep.

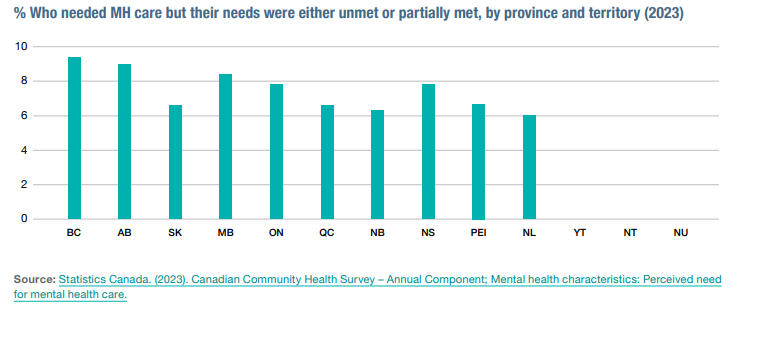

Mental health organizations recommend seeking help if symptoms last longer than two weeks or if you experience any feelings of self-harm or suicide. But with the state of the provincial healthcare system, many are left suffering on their own until spring.

More than 6.7 million Canadians struggle with their mental health. In fact, one in two have—or have had—a mental illness by the time they reach 40 years of age. An unprecedented number of young people are on antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications just to make it through the day to day in our present world. Yet mental health funding is falling behind.

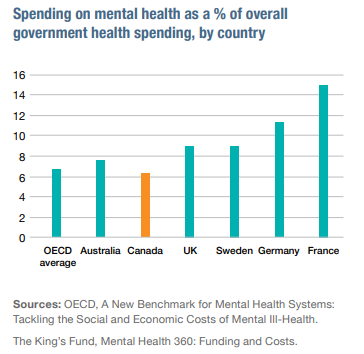

The 2024 State of Mental Health in Canada report from the CMHA concludes that Canada spends six per cent less than what peer countries – including France, Germany, the UK and Sweden – spend on mental health supports. In fact, Canada is spending seven to nine per cent less than what its national mental health strategy says it should be spending.

It has left many in a situation where help is out of reach.

“There’s no care outside of crisis and maintenance, and I’ve lived in that space a lot in my life,” a resident of Alberta said to CMHA in interviews conducted around the release of the report.

While Nova Scotia is the only province that mandates the reporting of wait times for mental health care, research suggest that across all provinces those times are increasing.

For all ages, the average wait times across Canada for mental health services is 22 days, according to the Canadian Health Institute for Health Information. But those wait times can increase for young people and depending on the service required.

In Ontario alone, youth are waiting between 600 and 900 days on average – approximately two and a half years – for psychiatric services, according to research from Western University.

“I see so many people going through quick-fix services and it’s so depressing because they should be getting real help,” a respondent from Saskatchewan told the CMHA. “They need help badly, and we’re failing them.”

The Ontario budget suggests the province will spend approximately $2 billion, or just shy of six per cent of the total health budget, on mental health in 2024-2025. But Canada’s Mental Health Strategy argues that number needs to be raised to nine per cent, which in Ontario means about $5.7 billion.

But while the big picture reality might be grim, respondents to the CMHA interviews noted the benefits of localized efforts to increase mental health supports.

“If you’re walking down the street and all of a sudden, you’re hit with this overwhelming anxiety, you can just walk in [to the community-based centre], and that’s what’s being done right,” the Vice Chair of CMHA’s National Council of People with Lived Experience, said.

One of those community-based responses is the City of Ottawa’s ANCHOR pilot in Centretown. The Alternate Neighbourhood Crisis Response (ANCHOR) program is a mobile crisis service that supports individuals experiencing a variety of complex health needs, but where emergency responder intervention may not be appropriate or beneficial.

Built from Ottawa’s Guiding Council on Mental Health and Addictions, the program focusing on collective impact and prioritizing effective communication.

The pilot remains part of the City’s plan to implement a safer alternate response to mental health, guided by the strategies included in the city’s Community Safety and Well-Being Plan and 2023–2026 Strategic Plan.

Anyone who may be in crisis and in immediate need of help should call 911. Other mental health helplines available to all Canadians include:

Suicide Crisis Helpline

9-8-8

Kids Help Phone

1-800-668-6868 (toll-free) or text CONNECT to 686868

Hope for Wellness Help Line

Call 1-855-242-3310 (toll-free)