Ottawa woman launches online community connecting motherless daughters

Posted Aug 25, 2020 01:30:00 PM.

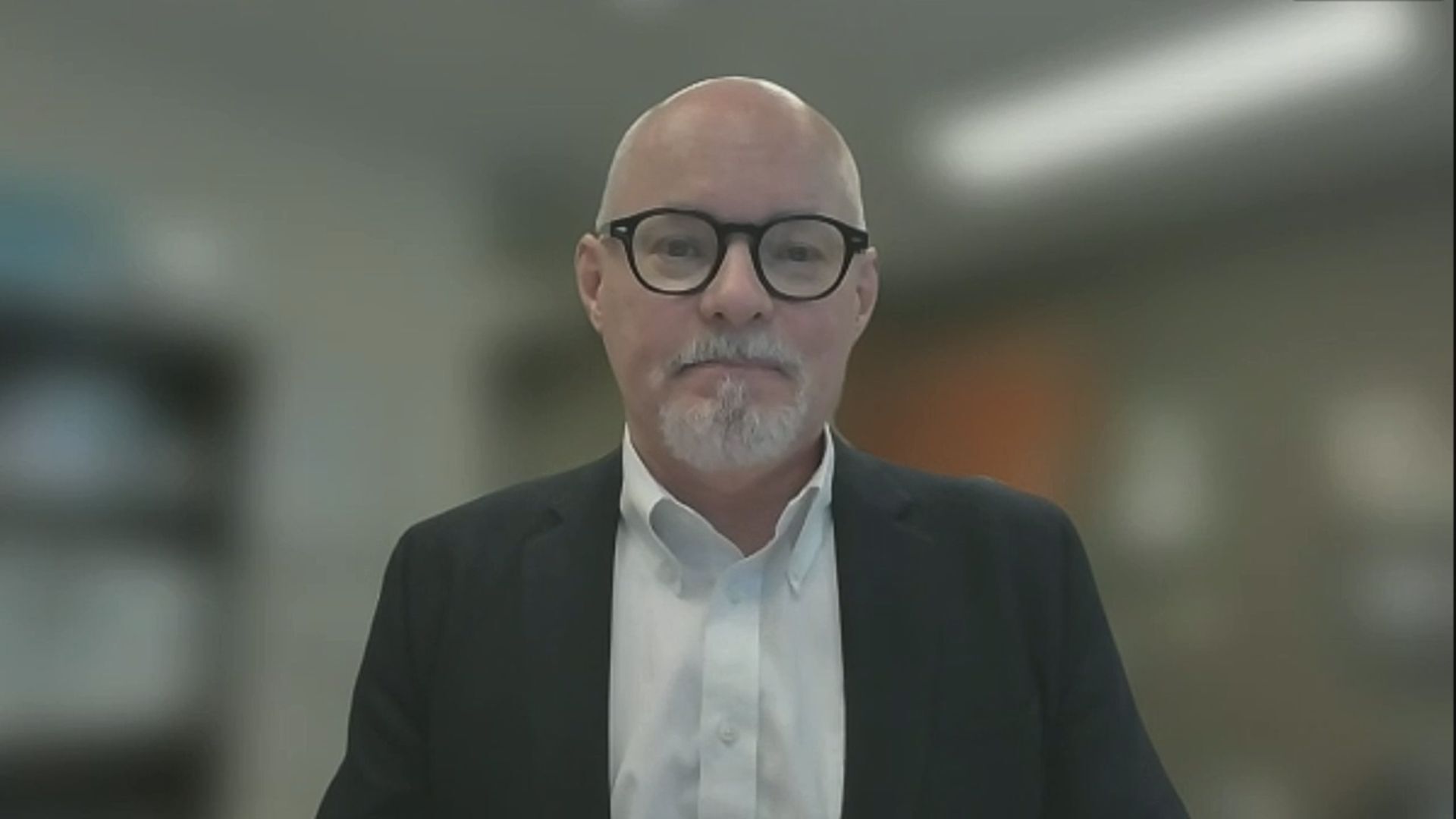

Instead of celebrating achievement on her high school graduation day, Janet Gwilliam-Wright was experiencing a completely separate defining moment in her young life — the death of her mother, Cass, at age 49 after a five year battle with breast cancer.

Twenty-five years later, she has lived longer without her vibrant, stylish, shoe-loving mom than she did with her. Commemorating her mother’s life, and honouring her own healing process, Gwilliam-Wright launched the Motherlove Project on June 17, an online platform for motherless daughters to share in an experience that can feel extremely isolating.

“It was pretty awful actually. I think I still have trauma just thinking about it now, being so young when she died,” explains Gwilliam-Wright.

Although separated by so many factors, like geography, culture and race, the nine women who thus far have submitted personal stories to the Motherlove Project share in the loss of a very particular connection, one exclusive between mothers and daughters, and one that only becomes more apparent, and compounds the original loss, when they become mothers themselves.

With two daughters of her own, Gwilliam-Wright says, “It becomes very visible once again – that your mom is not there to support you through one of the biggest life transitions that you could possibly go through, in becoming a parent.”

Shining a light on grief, an aspect of loss that society often shies away from, Gwilliam-Wright has found herself as a curator of sorts for the Motherlove Project, and hopes to eventually compile the collected stories into a book.

“It’s really been quite profound. It’s really powerful. We’re creating community through loss and it’s been really therapeutic for me to be able to do this.”

Although loss is the central theme of the Motherlove Project, Gwilliam-Wright wants women to know that the ability to share in this experience isn’t limited to death, but can also manifest through any means of forced separation like adoption, abandonment or estangement.

The idea that certain losses are prioritized over others is one of the reasons she launched this project in the first place.

“There’s still a real stigma about mothers who die from drugs and alcohol, or mothers who die by suicide, or mothers who have given up their children for whatever reason. I’m trying to position this as a platform for all those experiences to be shared and to be honoured and to talk about all of the conflicting emotions that come from wanting your mom but also being really mad at her.”

Because, says Gwilliam-Wright, her mother wasn’t perfect either. And the idea that many mothers are sanctified after their deaths made it challenging for her to reconcile the negative emotions she was experiencing with the pressure to feel a certain way. An important part of the healing process was learning, and accepting, that her mother was only human, even though, for a young Gwilliam-Wright, at times she seemed more super-human.

“She was an incredible force in her profession,” explains Gwilliam-Wright of Cass, one of the first women in British Columbia's advertising industry to reach the executive level. “She was so glamorous. I thought that she was larger than life. But I was also really mad at her a lot. She made a lot of really poor choices.”

Running from her grief instead of processing it led to a long road of mental health issues after Gwilliam-Wright was diagnosed with depression at age 24. But with the help of a great therapist, she’s finally been able to get back on track over the last five years, and she only hopes that by sharing these stories with other women who are experiencing mother loss, in whatever form, they can connect, sustain hope, and move forward together.

To submit a story, and for more information, follow the Motherlove Project on Instagram.