Remember This? The Bytown Consumers Gas Company

Posted Mar 22, 2021 01:49:00 PM.

CityNews, in partnership with the Historical Society of Ottawa, brings you this weekly feature by Director James Powell, highlighting a moment in the Ottawa's history.

March 25, 1854

For millennia, cities, stores and homes went dark after sunset. Artificial lighting was limited to the illumination provided by fireplaces and torches of various description.

Outdoors, wealthy pedestrians might hire a link-boy who, for a small fee, might carry a flaming brand to light their way. The alternative was the feeble light cast by a lantern, or making do with moon and star light.

At home, candles made of tallow from rendered beef, mutton or pig fat, which cast a sputtering and smelly glow, were widely used. Also popular and inexpensive were rush-lights made from the pith of the rush plant dipped in grease. The poorest had to be satisfied with a saucer of grease and a twist of cloth. The wealthy could afford sweet-smelling, beeswax candles.

Regardless, evenings must have been dim and shadowy, the light uncertain.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, burning oil derived from the rendered blubber of whales became popular owing to the bright light such fuel provided. The right whale, so-called for being a slow swimmer, which made it easier to catch, and its propensity to float after being harpooned, was the preferred catch. Sperm whales were also prized. Top quality sperm oil, also called spermaceti, was used to make candles given its waxy nature and lack of smell. The spermaceti organ of a sperm whale could contain as much as 1,900 litres of this valuable commodity—the reason why these great beasts were hunted to near extinction along with their right whale cousins.

In 1850, whale-oil lamps were placed over public wells in Bytown’s Upper and Lower Town.

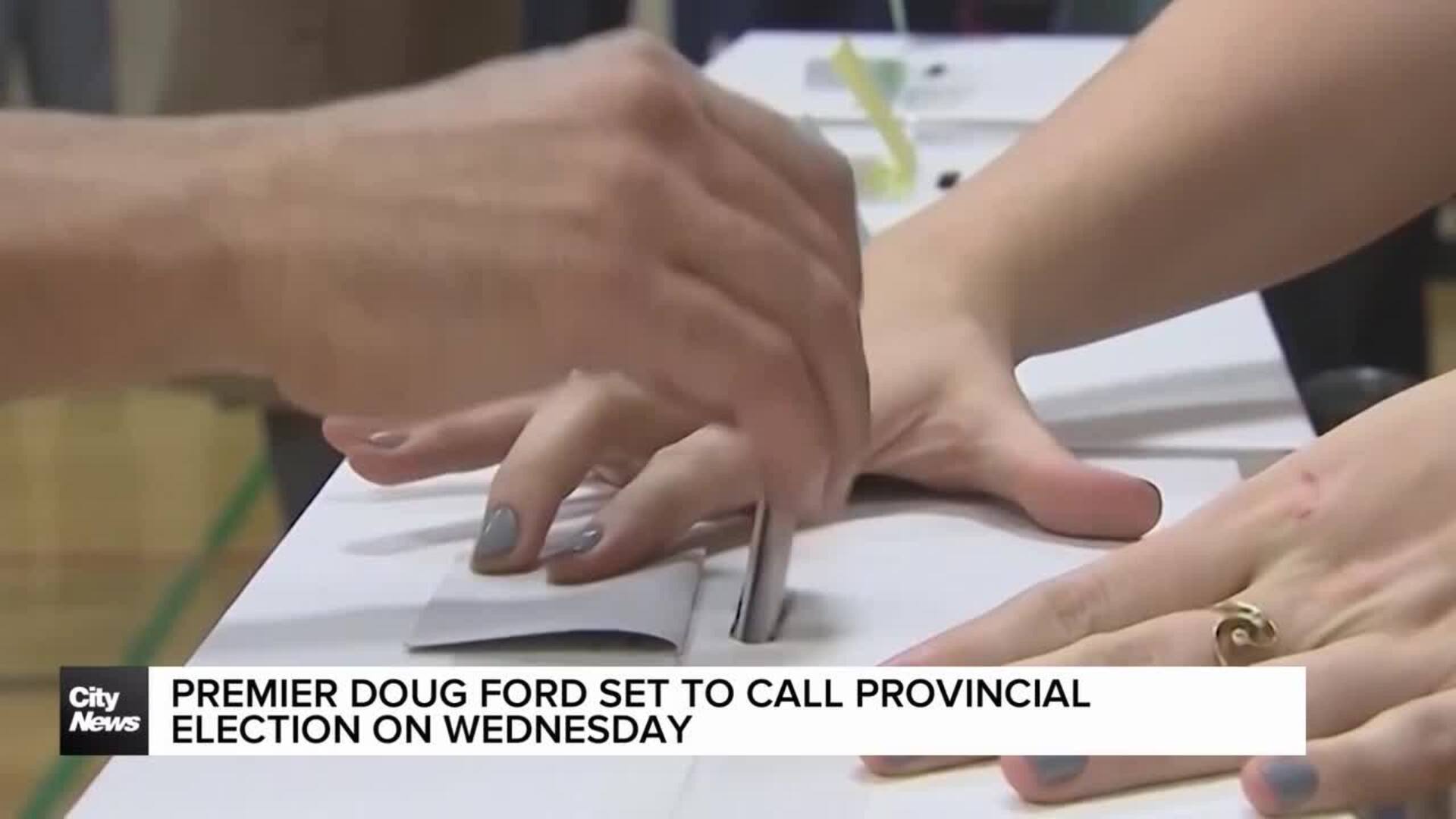

Notice that appeared in the Ottawa Citizen, 25 March 1854

A new lighting alternative came to the fore during the first half of the nineteenth century, first in Europe then in North America.

This was manufactured gas, sometimes called coal gas.

Manufactured gas was made by distilling black, bituminous coal in a heated retort. (A retort is a closed vessel made of glass or metal.) The vapour was then cooled and purified. The resulting gas was then stored and conveyed to consumers via underground pipes. Manufactured gas was first used for lighting in Europe during the early nineteenth century.

Reportedly, by the mid-1820s, most English towns of any significance were lit by gaslight. The technology crossed the Atlantic, with Boston and New York both furnished with gaslight by 1825. Gaslight came to Montreal and Toronto during the 1840s.

In 1854, Bytown’s leading citizens thought their community was sufficiently large to make a gas works in the town a paying proposition.

Although Bytown boasted a population of only 7,000, the town had great prospects. Area politicians hoped to convince the government that Bytown would make a fine capital for the new Province of Canada. Twenty prominent electors requested that Mayor Friel hold a public meeting “on the propriety of getting up a Gas Company for the town.”

In early March 1854, a Town Hall Meeting, chaired by the mayor, was held to discuss the issue. Six resolutions were passed. First, it was resolved that the inhabitants of Bytown were of the opinion that the bringing of gas to the town was “of considerable importance, both socially and economically.”

Second, a joint-stock company should be established to be called The Bytown Consumers Gas Company. The resolution also asked for the support of the Mayor and the Corporation of Bytown of an application to the Provincial Legislature for the necessary powers.

Third, it was resolved that the population of Bytown was sufficiently large and wealthy to make a gas works a profitable investment.

Fourth, it was agreed that a “book” be opened immediately to take subscriptions for stock in the new company, and that an application be made to the Provincial Legislature for an act of Incorporation.

Fifth, it was resolved that a Committee be formed to obtain subscriptions in the new company, and that a meeting of stakeholders would be called to organize a company once £2,000 ($10,000) had been collected. The Committee would include three area members of the Provincial Parliament—G. B. Lyon, E. Malloch, and John Egan—as well as the current mayor, Henry. J. Friel, as well as Alexander Workman, and Joseph-Balsora Turgeon, two prominent politicians who would later become mayor.

Sixth, the citizens agreed that the new gas company should have a capitalization of £10,000, divided into shares of £10 each.

Events moved quickly.

Three weeks later, it was official. A notice dated March 25, 1854 appeared in the Ottawa Citizen announcing that an application would be made to the Parliament of Canada at its next session to incorporate The Bytown Consumers Gas Company. It also serviced notice that it would request the ability to dig up roads for the purpose of laying pipes and to be able to hold property and undertake whatever was required for the manufacture of gas.

The following month, a declaration of intent to establish a gas company in Ottawa was registered in the Registry Office of the County of Bytown and sent to the provincial secretary in Quebec. This declaration was required under legislation passed the previous year entitled An Act to provide for the formation of incorporated Join Stock Companies for supplying Cities, Towns and Villages with Gas and Water (Victoria 16, Chapter 173).

The act set out the objects of such firms, their rights and obligations. Such rights including the laying down of pipes under public roads so long as they caused no unnecessary damage and permitted free and uninterrupted passage along the streets when the works were underway. The Act also required a gas company to locate their gas works so as not to endanger public health or safety. Consistent with the provincial act, Mayor Friel signed By-law 110c a few days later giving the Bytown Consumers Gas Company the authority to dig up Bytown’s streets and squares to lay down its gas pipes consistent with the provincial legislation.

Later, the Ordnance Department gave its consent for the company to install gas pipes along Sappers’ Bridge over the Rideau Canal subject to a nominal rent and the company’s agreement to remove the pipes if requested.

At the beginning of May, sufficient funds had been raised to require the meeting of stakeholders as specified under the fifth resolution approved the previous March. Subscribers to the capital stock of the company met in the office of John Bower Lewis, the second mayor of Bytown (and future first mayor of Ottawa). There, the senior officers of the company were elected: Dr, Hamnet Hill as President; Alexander Workman as Vice-President; and C. H. Piney as Treasurer/Secretary. A corporate seal for the company was adopted, and a corporate by-law was passed authorizing the opening of a stock book.

The first task of the company’s trustees was to find an expert to provide advice on building a gas works. They hired W. R. Falconer of Montreal to make estimates, plans and specifications.

Within three weeks, Falconer had submitted his report. He estimated that the cost of the proposed gas works would be £8,310, including the £300 needed for land on which to build the plant. He recommended that while all the tanks and buildings could be erected that summer, the pipes should be laid the following spring, with the works in operation by August 1, 1855.

Subsequently, a Mr. A. Perry of Montreal submitted a tender for the contract according to Falconer’s specifications.

To the disappointment of the shareholders in the Bytown Consumers Gas Company, his price to do the work came in at £8,375, excluding the cost of purchasing the necessary land for the gas works.

Perry, however, must have liked the company’s prospects. He submitted a supplementary tender offering to buy £1,000 of the company’s shares and to loan it a further £3,000 at 6 per cent per annum for ten years.

The trustees demurred, of the view that Perry’s financial offer was too expensive. They did, however, find a suitable piece of property for £500 that they believed was large enough to accommodate the gas works and allow for future expansion.

However, at a meeting of stockholders held in August 1854, President Dr. Hamnet Hill revealed that the take-up of shares in the Company had been discouraging. Only £3,925 had been raised locally, and no Montreal investors had been found. He was disappointed that people who had said they would subscribe for shares had subsequently backed out, or had bought a smaller amount. He recommended two options to shareholders. Either they wait until “other persons of enterprise” came forward, or dissolve the company and return the investments of people less the costs already incurred.

What exactly happened next is unclear.

There is a brief reference in the Ottawa Citizen in September 1854 to the effect that Bytown had “decided against a gas works.” However, in December 1854, the company was still around with the press reporting on a major shake-up of the firm’s senior officers. Alexander Workman resigned as Vice-President and was replaced by Mr. J. M. Currier. Henry Friel was elected Chairman and Francis Clemow was appointed secretary. At the same meeting, it was announced that a site for a gas house had been purchased on King Street (now King Edward Avenue) between Rideau and York Streets for £500.

Somehow the necessary capital for the company had been found.

Pipes were laid through 1855, with the main line running under Rideau, Sparks, Sussex, York and Nicholas Streets. By the beginning of 1856, work had progressed sufficiently, despite “some trifling difficulties,” to permit the lighting of gas.

In mid-April 1856, the price of gas was set thirty shillings per thousand (presumably cubic) feet, payable at the end of each quarter. A 25 per cent discount was given for prompt payment. This was an astronomical price by today’s standard and was a source of complaint. The Bytown gas price was roughly 50 percent higher than the price in Montreal, which was $5 per thousand feet (20 shillings), less a 35 per cent discount (in 1859), twice the New York price and five times that of that in London. A lack of economies of scale owing to Bytown’s small size might have been a factor in the price differential.

By the early 1890s, Ottawa’s gas price had dropped to $1.80 per thousand cubic feet.

Advertisement for gas-lit chandeliers, Ottawa Citizen, 25 December 1860.

Notwithstanding the exorbitant price, gas street lights quickly lit Ottawa’s main streets, starting with Rideau and Sussex Streets.

Advertisements appeared in local newspapers urging wealthy homeowners to lit their houses with gas lamps.

In 1860, William Stevenson, a steam and gas fitter who operated out of Ogdensburg, New York advertised French and English chandeliers for sale in the Ottawa Citizen. He claimed his prices were cheaper than what could be obtained from Montreal, notwithstanding duties. He invited Ottawa residents to check out his store in Ogdensburg where he always had a large stock on display. He also offered a money-back guarantee. This was cross-border shopping nineteenth century style.

The introduction of gas has its downside: pollution.

The Bywash, which ran from the Rideau Canal down King Street to the Rideau River became fouled with tar and other refuse from the coal gas plant on the street. Fish deserted the creek and people could no longer drink or wash in it. There is a report of boys who went swimming in the Bywash being dyed a dark colour by the dirty water. Apparently, it took a month for the stain to wear off.

The Bywash was finally covered over and converted into a sewer. Of, course, the pollution didn’t go away. It was just hidden from view, and was still funnelled untreated into the Rideau River and thence into the Ottawa River.

In 1865, the Bytown Consumers Gas Company updated its name to the Ottawa Gas Company.

Twenty years later, it rapidly lost its lighting business to a new competitor—electricity introduced to Ottawa by Thomas Ahearn and Warren Soper. However, manufactured gas remained the fuel of choice for home stoves—electric stoves and ovens were uneconomic until the 1930s.

As prices fell over time, gas was also increasingly used for heating. In 1906, Ottawa’s electric and gas industries were merged into a giant lighting and heating monopoly called The Consolidated Light, Heat and Power Company controlled by Soper and Ahearn. This state of affairs continued until 1949 when, following a city plebiscite, Ottawa purchased the electrical side of the firm to form Ottawa Hydro, leaving the Ottawa Gas Company in private hands.

In 1957, Consumers Gas of Toronto purchased the company. The following year, natural gas was piped into the Ottawa area, and the production of manufactured gas ceased.