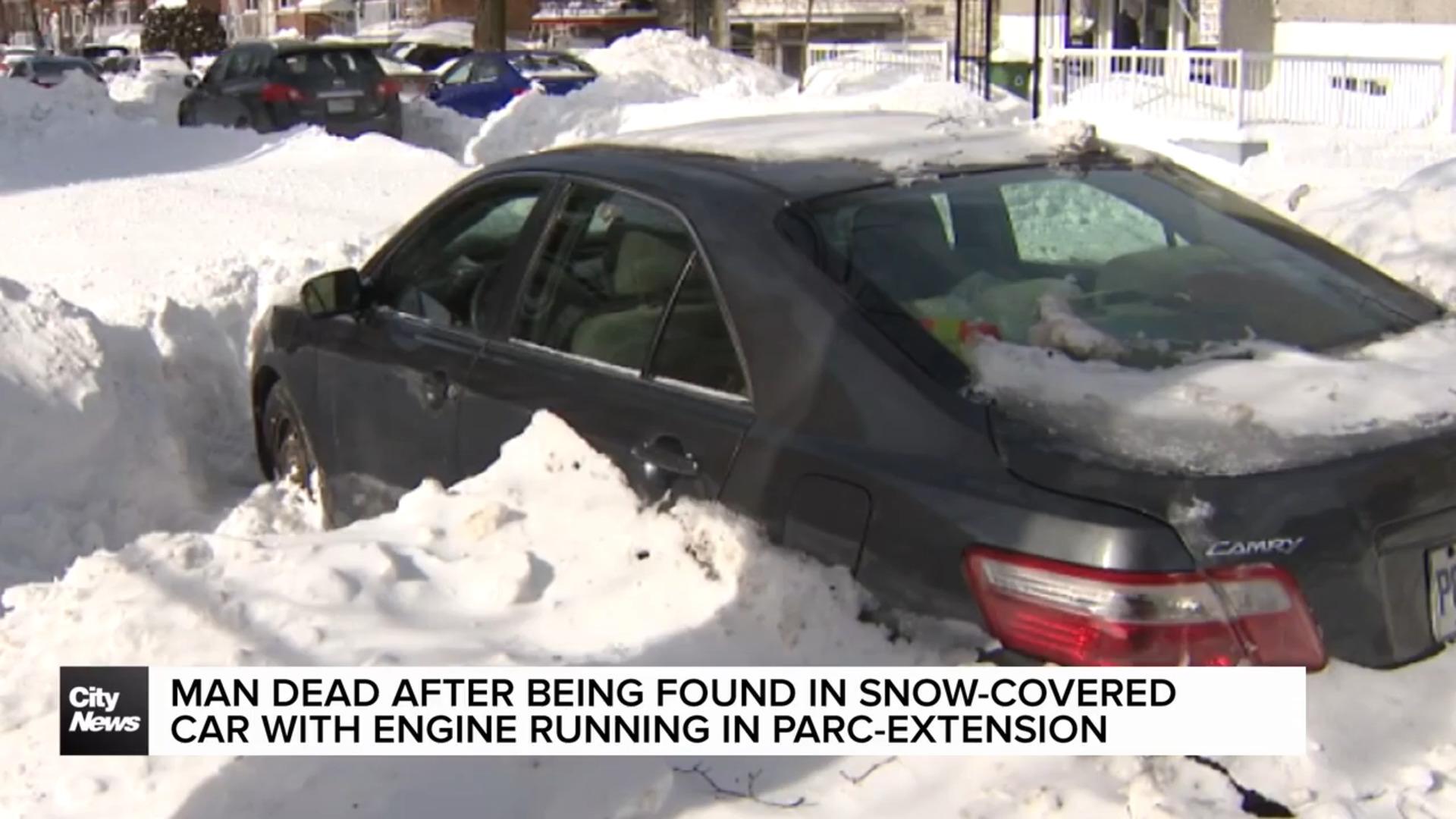

Opioid deaths highlight need to decriminalize hard drug possession, Canadian police chiefs say

Posted Jan 29, 2021 03:24:00 PM.

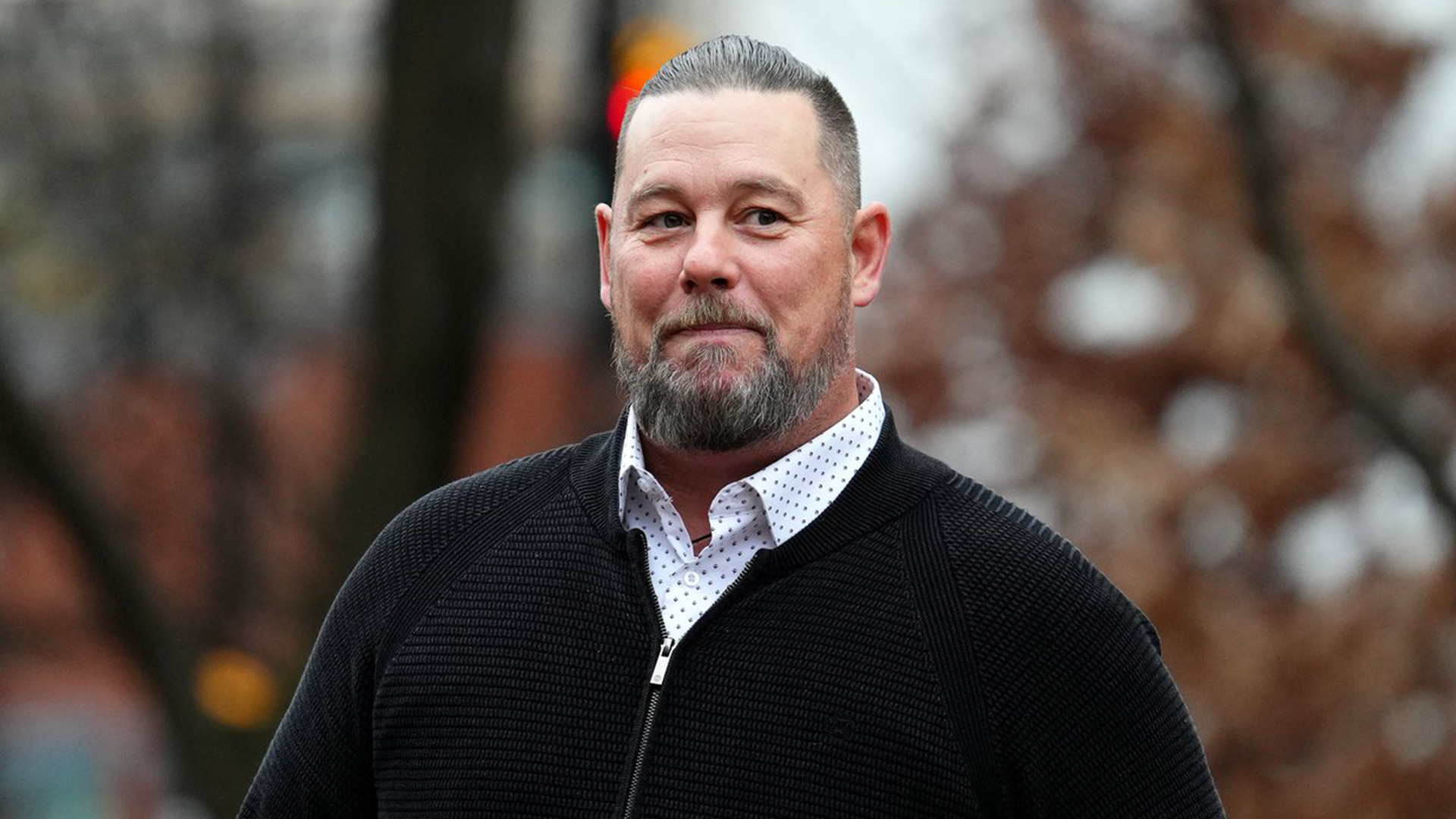

The scourge of overdose deaths underscores the need for Canada to decriminalize simple possession of hard drugs, says the president of the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police.

In urging action, Bryan Larkin noted that overdose deaths are outpacing those from the COVID-19 pandemic and homicides in British Columbia, and likely Ontario.

“Over the last six years, 18,000 Canadians have lost their lives to drug addiction,” Larkin says. “If 18,000 people lost their lives in traffic collisions, our country and our communities would not accept that. There would be outcry.”

The association president made his comments at a virtual forum called “Policing 2021,” on Thursday. The issue of decriminalization — as was the case with cannabis — is “polarizing,” both within society and within police ranks, he says.

Like many others, Larkin says he was raised to believe “drugs are bad and people who use drugs are criminals.” But criminalization, he explains, has disproportionately affected the marginalized and people of colour, and there's now an awareness that addictions are a mental health issue.

Ottawa Police Chief Peter Sloly agrees that police need to become a “diminishing” element when it comes to dealing with people in mental health crises. While police will always have some role in such responses, there needs to be a different model that takes in social services, education and the health-care sector, he says.

“We've been not just the last resort, but often the first resort on these types of incidents,” Sloly told the forum. “We've become a bit of a Swiss Army knife.”

Sloly cites a program in Eugene, Oregon, where up to 90 per cent of mental health calls are handled without hard police intervention, although such changes take years to implement successfully, so he warns against moving too quickly.

“There's a group of people out there who believe that police should have nothing to do with mental health services,” Sloly says. “I just don't think it is practical.”

Ottawa's chief says there were three calls within a 24-hour period this week, in the capital, where armed people had barricaded themselves and all three required police response.

“Armed with scissors, machetes and edged weapons, all of them in mental health crisis, in three different parts of the city.”

The chiefs also acknowledges systemic racism in policing, but says the issue is no longer being swept under the rug. At the same time, Sloly adds, simply addressing the issue within police services won't fix the wider problem.

“We're still going to have the conditions that produce crime and victimization, marginalization and discrimination,” he says.

And to that, Sloly says he's in contact with counterparts like Dr. Vera Etches, Ottawa's chief medical officer of health, and Camille Williams-Taylor, the director of education at the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board to make meaningful change in an integrated approach.

— With files from The Canadian Press